Underrated Artefacts: The Bird Ring

Medieval Hawking, the Rise of Pigeon Racing, and a Call to the Frontline

‘Roasted Swans’ (a special treat of Henry VIII’s), ‘Blackbird Pie’ (a 16th Century banquet spectacle), and ‘Robins on Toast’ (a very popular 19th Century US dish) - humans have been enjoying our wild birds for centuries.

But today it’s far more common to spot a bird sporting a fashionable anklet - with the ringing of wild birds in Britain beginning in 1909 to track bird migration, breeding and populations - than it is to find a robin on your dining table (Unless it’s a new change of direction for KFC!). And this ringing of birds wasn’t a new idea, we’ve been ringing birds for centuries (as well as eating them) and there’s much to be said for the discovery of a simple bird ring.

Medieval Hawking

The Medieval Hawking ring, a silver ring that wasn’t worn by humans…

Falconry is one of the oldest known human activities, and it is considered today as one of UNESCO’s Intangible Cultural Heritages of Humanity in 17 countries and across 3 continents. It’s been found in the bas-reliefs of the palace of Sargon II (722–705 BC), has been released into battle by the Anglo-Saxon chieftain Byrhtnoth (991 AD) and sailed across the English Channel with William the Conqueror (1066 AD). And by the time of the Middle Ages, falconry was more popular than ever; a sport of sovereignty, status and diplomacy.

To start with, it was known as the ‘sport of Kings’ notably enjoyed by Athelstan, the first Anglo-Saxon King of England; Edward III who splashed out over £600 on falconry in 1368 AD; and quite famously Henry VIII. Yet, whilst you needed to be moderately prosperous to engage in the world of falconry, this didn’t stop it from becoming incredibly widespread amongst society. It was even a sport for women, appearing on the seals of Eleanor of Aquitaine and written about in the 15th Century ‘Book of St Albans’ by prioress Juliana Berners.

Essentially, you would be pretty hard-pressed to travel anywhere in the Middle Ages without spotting a bird on the arm of a passer by in the street - or carried by a servant for a lady - and the bird could tell you a lot about their social standing…

The Bird of Prey Social Hierarchy

Emperor - Golden Eagle

King - Gerfalcon

Lord - Peregrine Falcon

Knight - Saker

Esquire - Lanner

Yeoman - Goshawk

Of course, this social order didn’t stop aspiring merchants buying out of their social bracket to advance their status, nor did it prevent the King from keeping a fine collection of Goshawks and Peregrine Falcons.

Check out this incredible Lincolnshire example of an Edmund Hall of Gretford, (today known as Greatford), dated from 1510 - 1592 AD. Rights Holder: Cambridgeshire County Council

CC License:

Just one trained ‘raptor’ - as these hunting birds of prey are known - was expensive to train and maintain, a treasured possession, and a costly good. But that didn’t stop them being lavishly spent on by their owners, with special perches made for them in bed chambers, and, most importantly, silver rings - known as ‘vervels’ or ‘hawking rings’. These rings attached to thin leather straps, known as ‘jesses, which were tied round the bird's legs, making them easier to handle; but they weren’t just a lavish expense, inscribed with the owners name and place of residence, they also provided an important identity if the bird ever got lost (you didn’t usually have to worry about your bird being stolen however, as this was an act punishable by death - at least in the reign of avid falconer Edward III). Today these silver rings still do exactly as they were intended, introducing us to the lives and society of Medieval people centuries down the line.

Pigeon Racing

You could say the first instances of pigeon racing occurred in cities under siege, where pigeons seem to be naturally equipped to send communications to the outside world. And this is something that’s even recorded in Roman times, during the Battle of Mutina (43 BC) in Pliny the Elder’s Natural History. But it isn’t until 19th Century Europe that the pigeon really gets its time in the limelight.

Not a Pigeon Ring but check out this incredible Roman Pigeon Artefact - Much like their later use for Pigeon Racing, Pigeons were an important symbol of communication throughout the Roman Empire. Rights Holder: The Portable Antiquities Scheme

CC License:

Pigeon racing began small in working-class culture. It was short-distance local entertainment enjoyed by the likes of Derbyshire miners, Spitalfields weavers and the residents of London’s Bethnal Green. Betting was naturally an integral part of the race, but it would be the pigeons who won over the hearts of the working-class, becoming more than just entertainment; as a hobby, family bonding activity, and bringing the community together.

So it’s no surprise that the upper classes soon caught wind of this flight of fancy, introducing more challenging and complex long distance races that involved travelling by train to a set point for release. By 1898 the sport had grown so enormously that the first Pigeon journal, The Racing Pigeon, was released; a pigeon gift by King Leopold of Belgium had garnered a Royal interest with races undertaken at Sandringham; and the volume of ‘pigeon traffic’ on the railways was so great that some companies even introduced ‘Pigeon Specials’.

But how were these races monitored? Of course this was all down to the humble pigeon ring - a ring that carried an individual identity number - and once a safe flight had been made home, an identity which was recorded at the local post office or pub to keep the scores. It wouldn’t be too long however, before the Pigeon Race found itself drafted into a much more pressing service…

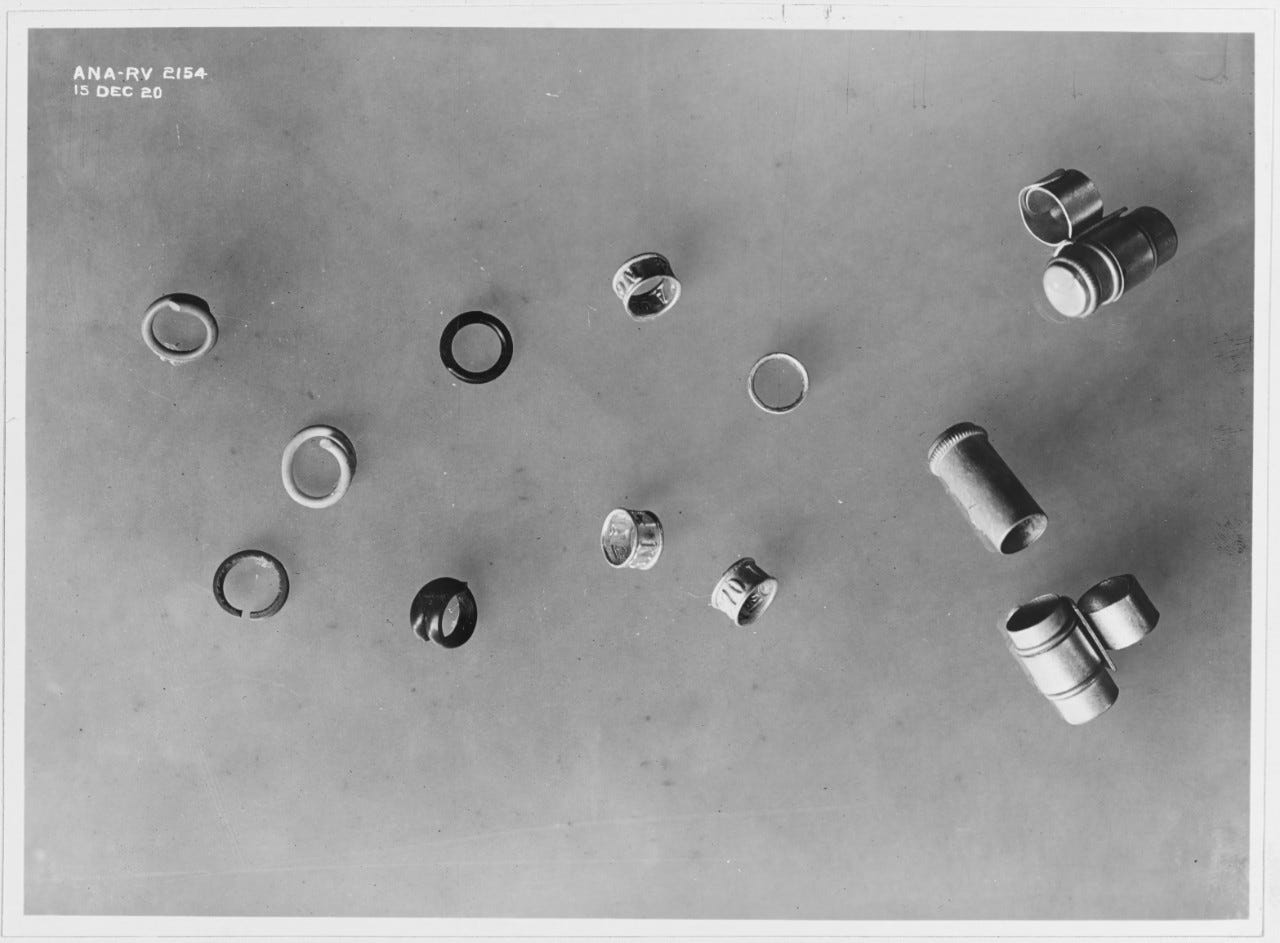

Identifying Pigeon Rings:

Helpfully all pigeon rings conform to the same standard formula:

Organisation Abbreviation / Year of Registration / Registration Letters of the Pigeon Club / Pigeon’s Unique Identification Number

Example: GB 08 AB 12345

Pigeon Rings. Leg color bands, December 15, 1920 U.S. Navy photograph

Wartime Pigeons

The outbreak of World Wars in both 1914 and 1939 saw thousands of pigeons and pigeon fanciers called into service - including those from the Royal Loft.

Much like in the early sieges that saw pigeons first take to the skies with messages, their potential for covert and effective communication was realised. Over a quarter of a million pigeons (100,000 in WWI and 250,000 in WWII) served during the World Wars. All pigeon racing was suspended, pigeon corn was rationed and the birds of prey along the coast of Britain were culled.

Used by the Army, the RAF and the Civil Defence Services, a pigeon passing by could be carrying secret messages or urgent information that saved the lives of trapped or downed servicemen on the frontline. And they weren’t just used here in Britain, with pigeons serving under American, Canadian and even German forces. They were parachuted into Renaissance fighters in France, Belgium and Holland; and carried in special watertight baskets by RAF bombers and reconnaissance aircraft, sent home with coordinates in case they had to ditch - often making the journey in extreme circumstances.

‘Reliability is the most desirable characteristic of the homing pigeon. Records disclose that 99 percent of the messages sent by pigeons during tactical operations are delivered successfully.’ - Signal Pigeon Company Handbook, published by the United States War Department in 1944.

Countless numbers of these pigeons saved lives, a fact shown by the 32 Dickin Medals that went to pigeons out of 53 - the animal equivalent of the Victoria Cross - presented during WWII. It’s impossible to share every heroic story of these pigeons, but we will mention a few notable achievers here:

Pigeon Veterans

GI Joe - Saved thousands of British troops who took an Italian town from the Germans after a bombardment by the USAF. With radio contact down and flying at 60 mph back to his base, GI Joe’s message of success arrived just in time to call off a further bombardment of the town that would have killed all.

Royal Blue - A pigeon from the Royal Lofts who was the first pigeon to bring a message from a force-landed aircraft on the continent; flying 120 miles in 4 hours, 10 minutes to pass on vital information about the situation of the crew.

White Vision - A RAF Catalina boat had to ditch in the Hebrides, all sea and air rescue operations were impossible due to incredibly bad weather and thick mist. Flying over 60 miles, over heavy seas, with limited visibility at less than a hundred yards and against a headwind of 25 mph, she returned home with her crew's position prompting their successful rescue.

United States Naval Reserve (Women's Reserve) WWII U.S. Navy photograph

The humble ‘Bird Ring’ can be an artefact often disregarded as a piece of detritus, but every single one contains a story trapped within the information written on its surface, one that deserves to be uncovered.

Wow I love this story!

That's v interesting. My last bird ring was last month detecting aluminium and had 1935 written on it and a number 25. I have kept them lately, but thanks I hadn't realized their relative value. I just read an article that says possibly proteins in certain animal's eyes called cryptochromes orient their field of view in accordance with the Earth's magnetic field so they use visual cues and this compass view together to navigate. I think I also read they got disorientated during mass coronal ejections from the sun which interferes with the polarisation of Earth's field.