The sceat which started it all—A Series E, ‘Plumed Bird’ Continental Issue.

A chance discovery of an Anglo-Saxon Sceat less than a year into our metal detecting adventures sparked a bit of an unhealthy and ongoing obsession, which we still can’t shake nearly 5 years later—and hopefully by the end of this newsletter, you’ll understand why!

The Collapse and Return of the Monetary Economy

First, we need to take you back to a time when the Romans upped and withdrew from Britain, leaving the frontiers undefended and threatened by the Picts and Scots—after the Romans had spent centuries keeping them at bay. In desperation, the Britons reached out for help (they’d tried tempting the Romans back to no avail), turning to the Anglo-Saxons—who in the final period of Roman rule, had been raiding Britain’s shores—inviting them in, sparking the start of the Anglo-Saxon Invasion.

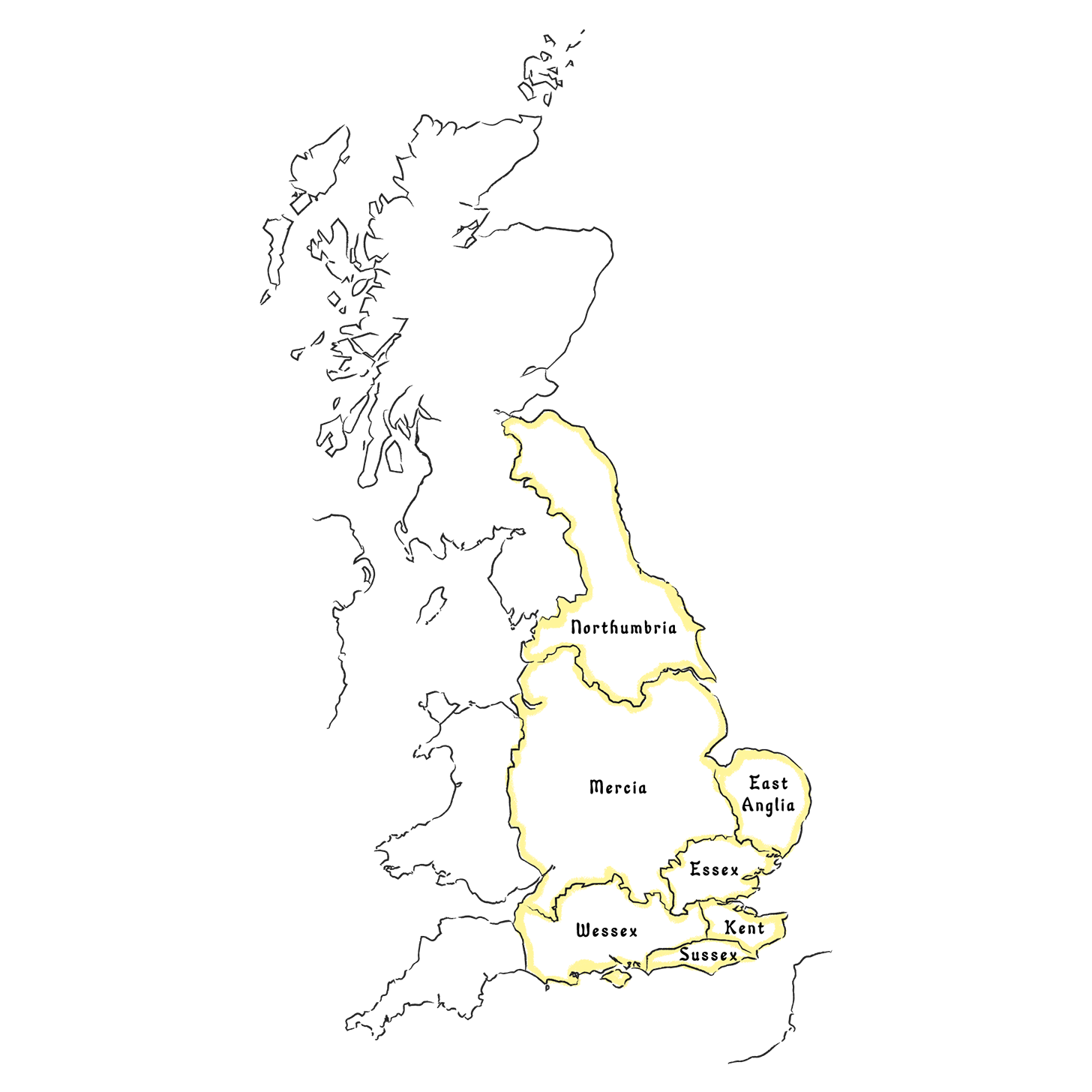

This group of Germanic invaders and settlers would go on to found the early beginnings of ‘England’ as we know it today (See illustration below). But what you don’t realise is how fragmented these early Anglo-Saxon settlers were, they weren’t a single nation (this came much later after many wars), they were a collection of tribes (mainly made up of the Angles, Saxons and Jutes), and they had no economic need for money, much preferring to barter and trade instead.

Therefore, Britain experienced a nearly 2 century wide gap in the use of coinage, following the withdrawal of Roman rule, developing a shortage of silver and gold—and the best way to replace the coffers was through accepting foreign currencies in trade. Initially, these coins were used as bullion or transformed into jewellery; but with the growing development of trade with the Continent, and the political and religious need, following the conversion to Christianity, progressed—the benefits of having a currency began to outweigh this pre-existing societal norm brought in by the Anglo-Saxons.

The Anglo-Saxon Heptarchy (7 Kingdoms) of Britain: Northumbria, Mercia, Wessex, Sussex, Kent, Essex and East Anglia.

What is the Anglo-Saxon Sceat?

The Anglo-Saxon Sceat—or Sceatta as they are formally known—are quite the numismatic enigma. A strange, entirely silver coinage that emerged from a society, just getting its head around the idea of currency. Bearing little to no inscriptions, or text of any kind, these wide-ranging, fingertip-sized, roughly circular coins instead immerse you into an iconographic world, one full of mythical beasts, fearsome gods and the tentative emergence of Christianity—it’s entirely the stuff of historical fantasy.

Initially, the Anglo-Saxons merely dabbled with the development of coins, producing limited gold coinage stylistically borrowed from their predecessors and playing into the deep-rooted feeling of ‘Romanitas’ (the spirit and fond memory of Rome) still circulating amongst the Britons—and Romans—left behind.

But by 680 AD, a pivotal shift saw an entirely new currency flood the South and Eastern parts of the country—the arrival of the Sceat. This currency was produced and circulated both here in Britain and by our North Sea trading partner, the Netherlands, as a key means of exchanging silver bullion—and for an entire currency to be developed and minted by both parties, the Anglo-Netherlands trade at this time must have been prolific.

Check out this early Anglo-Saxon Gold Tremissis, found in Kent, of the ‘Two Emperors’ Type—a variety inspired by Roman coins depicting the Goddess Victory

The Sceatta Timeline

This currency developed in two main phases, at different times and in different parts of the country.

The Primary Phase (South 660s–710 AD / North 685–704 AD)

Conservative styles with a strong sense of ‘Romanitas’

The Secondary Phase (South 710–750s AD / North 737–829 AD)

Innovative styles and the influence of the Conversion to Christianity

A Mythical Puzzle

No one knows what value these Sceats would have possessed, or even understands the true meaning behind the wide range of imagery appearing on them. From the birds, four-legged beasts, writhing serpents, spiky-haired busts, god-like human figures, horned death masks, votive standards, and crosses. They appear to have been influenced by a multitude of cultures, from Roman, to Byzantine, Frankish, Christian, and Pagan—a true unconventional blend of motifs.

Perhaps this was the whole point? Minted to circulate amongst several settlements of Anglo-Saxon tribes, and traded with the continent, this diverse range of consumers surely demanded a wide appeal from these coins. Incorporating a myriad of imagery on them, therefore, containing a little bit of something for everyone, and the clever reinforcement of the Christian message, in a way which also suggested continuity from the old ways. Here are 4 of our favourite examples:

Primary Phase, Series Z (680–710 AD)

A forward-facing portrait, heavily inspired by Byzantine coins, and conveying a ‘saint-like’ impression.

Primary Phase, Series B (690–710 AD)

A diademed bust evocative of the Roman Emperors who appeared for over a millennia on previous coinage.

Secondary Phase, Series N (710–760 AD)

Twin ‘standard bearers’, but unlike the militaristic ‘GLORIA EXERCITVS’ Roman type, these bearers clutch crosses, instead of swords and shields.

Secondary Phase, Series Q (710–760 AD)

A bird trampling a serpent, said to represent the battle between good and evil, here interpreted with the triumph of the bird.

Rediscovering A Forgotten History

The Anglo-Saxon Sceats stuck around for just over a century, their variants diluting with time in both precious metal and style; the sceats of the latter end degenerated into geometric symbols and abstracted interpretations of previous imaginative and complex styles. Eventually, they were reformed into the silver penny—the subsequent main coin type in England for half a millennium—and relegated as a product of the ‘Dark Ages’; a sweeping generalisation for the period the history books like to neglect.

As a forgotten ancestor of English coinage, today the Anglo-Saxon sceats suffer from a lack of knowledge and understanding, a shortage of examples on record and a high premium attached to those surviving the centuries in outstanding condition. So it’s not shocking that they represent a complex area of numismatic study.

But there is hope, the Aston Rowant hoard discovered in 1971—the largest single find of sceats in Britain, consisting of around 350 coins—redefined our understanding of this coinage, dividing it into the two clear distinctions of Primary and Secondary issues. This was the beginning of the metal detecting era, an important tool which must be harnessed for further archaeological study; and an advantage praised by prolific sceat numismatic Metcalf and fellow Laight, when considering the scientific, data-based advantages of the faithful reporting of a Bidford detectorist in the recovery of more than 50 sceats, in their article for the British Numismatic Society’s Journal in 2012.

Every reported metal detecting discovery provides a further glimpse into the hazy picture of this little-known world—we can dare to hope that one day, maybe we will stumble into the next big discovery for the Anglo-Saxon Sceat? After all, how will we become acquainted with this lost history if no one is out there looking for it?

Gold sceattas are enigmatic, I don't know if they've appeared in the catalogues yet. I'm not talking about the earlier tremessis coins it's just some of the silver sceatt designs have appeared in gold in Kent, not sure about elsewhere ..

I wish our coins were this interesting nowadays.